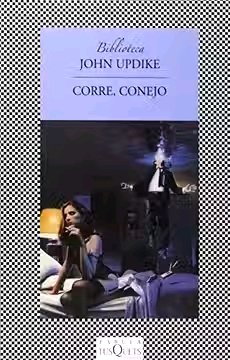

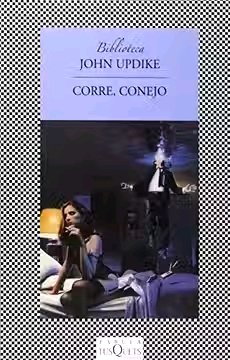

Corre, Conejo de John Updike 🇪🇸|🇺🇸.

Cada año manoseo esta novela como si entrara a un abismo. Seducido.

Hay libros que no se leen, se vuelven a leer. Corre, Conejo (1960) de John Updike es uno de esos. Cada vez que regreso a las páginas de Harry "Conejo" Angstrom —su protagonista atrapado entre la mediocridad y el deseo de huida—, siento que estoy a punto de caer en algo más grande que una simple historia. Es como abrir una puerta a un laberinto de preguntas: ¿Qué significa ser libre cuando todas tus decisiones te encadenan? ¿Es posible escapar de una vida que no elegiste o solo estás condenado a correr en círculos?

Interrogante

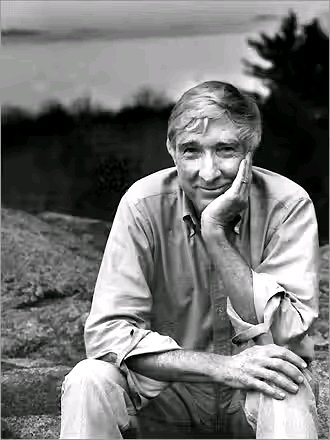

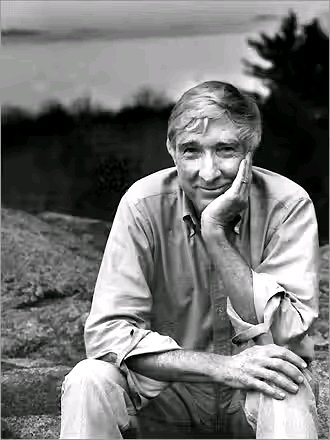

John Updike (1932-2009) no escribe para que sus lectores se sientan cómodos. Su prosa, precisa hasta lo obsesivo, no perdona ni idealiza. Conejo no es un héroe, ni siquiera un antihéroe romántico. Es un tipo común: un exjugador de baloncesto fracasado, un marido infiel, un padre ausente. Y, sin embargo, hay algo en su desesperación que nos resulta familiar. Porque Updike no juzga: solo muestra. Y al hacerlo, nos obliga a preguntarnos: ¿Qué tanto nos diferenciamos nosotros de Conejo?

La huida

Conejo, hastiado de su matrimonio y su trabajo mediocre, decide ir a buscar a su hijo… pero en lugar de volver a casa, sigue conduciendo. Sin plan. Sin destino. Solo el impulso de moverse, como si la velocidad pudiera salvarlo del vacío.

Esta huida sin rumbo es, en el fondo, el reflejo de una generación atrapada entre el sueño americano de posguerra y la creciente sensación de que ese sueño era una mentira. Updike no era beatnik ni existencialista, pero capturó como nadie esa angustia silenciosa de quienes se dan cuenta de que han seguido un guion que no querían.

Hiperrealismo.

Lo que hace única a Corre, Conejo no es solo su trama, sino cómo está escrita. Updike describe todo con una claridad casi dolorosa: el olor a cerveza rancia en un bar, la textura de la piel de una mujer, la luz del atardecer sobre el asfalto. No es realismo, es hiperrealismo. Y en medio de ese paisaje minucioso, los diálogos —aparentemente banales— esconden grietas emocionales.

El antídoto

Updike sigue siendo un antídoto necesario. Sus personajes no mejoran, no "aprenden la lección". Solo existen, con todas sus contradicciones. Leer esta novela es como ver desfilar seres imperfectos, a veces cobardes, a veces egoístas, pero siempre humanos.

Así que sí, cada año vuelvo a Corre, Conejo. Y cada año, el abismo me devuelve una pregunta distinta. Porque, como escribió Updike: "La felicidad no es un destino, es un camino"… aunque a veces ese camino no lleve a ninguna parte.

English

Every year, I handle this novel as if stepping into an abyss. Seduced.

There are books you don’t just read—you reread them. Rabbit, Run (1960) by John Updike is one of those. Every time I return to the pages of Harry "Rabbit" Angstrom—its protagonist, trapped between mediocrity and the urge to flee—I feel like I’m on the verge of falling into something far greater than a simple story. It’s like opening a door to a labyrinth of questions: What does it mean to be free when every decision you make only chains you further? Is it possible to escape a life you never chose, or are you just doomed to run in circles?

The Question

John Updike (1932–2009) doesn’t write to make his readers comfortable. His prose, precise to the point of obsession, neither forgives nor idealizes. Rabbit is not a hero, not even a romantic antihero. He’s just an ordinary guy: a failed ex-basketball player, an unfaithful husband, an absent father. And yet, there’s something in his desperation that feels familiar. Because Updike doesn’t judge—he simply shows. And in doing so, he forces us to ask: How different are we, really, from Rabbit?

The Escape

Rabbit, fed up with his marriage and his dead-end job, decides to go pick up his son… but instead of returning home, he just keeps driving. No plan. No destination. Just the impulse to keep moving, as if speed alone could save him from the void.

This aimless flight is, at its core, the reflection of a generation trapped between the postwar American dream and the growing sense that the dream was a lie. Updike wasn’t a Beat writer or an existentialist, but he captured like no one else that quiet anguish of those who realize they’ve been following a script they never wanted.

Hyperrealism

What makes Rabbit, Run unique isn’t just its plot, but how it’s written. Updike describes everything with an almost painful clarity: the stale-beer stench of a bar, the texture of a woman’s skin, the sunset light on asphalt. It’s not realism—it’s hyperrealism. And within that meticulous landscape, the seemingly banal dialogues conceal emotional fault lines.

The Antidote

Updike remains a necessary antidote. His characters don’t improve, they don’t "learn their lesson." They just exist, with all their contradictions. Reading this novel is like watching a parade of imperfect beings—sometimes cowardly, sometimes selfish, but always human.

So yes, every year I return to Rabbit, Run. And every year, the abyss throws back a different question. Because, as Updike wrote: "Happiness isn’t a destination, it’s a journey"… even if sometimes that journey leads nowhere.

Congratulations @marabuzal! You have completed the following achievement on the Hive blockchain And have been rewarded with New badge(s)

Your next target is to reach 150 posts.

You can view your badges on your board and compare yourself to others in the Ranking

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPCheck out our last posts:

Gracias por tus sugerencias y textos siempre de excelencia.

Cuánta enseñanza en el camino que llega gracias a ti.

Estupendo título que provoca motivarnos a consumir.

¡Gracias!

Gracias por traernos está lectura. 😘😘🙏👏👏👏

Después de leer este post le entran ganas de buscar el libro y descubrir por uno mismo lo que nos cuentas.

Gracias 👍