Los monstruos como encarnaciones de Miedos Colectivos (tema del domingo 15/6)/ Monsters as Embodiments of Collective Fears (Theme for Sunday, June 15th) (ESP/ENG)

El tema de hoy, "Mitos antiguos de diversas culturas afectando nuestra psicología, narrativa y cosmovisión", es uno que me gusta mucho porque se puede analizar desde muchísimas aristas. Hoy les hablaré del miedo, de los temores arquetípicos, por decirlo de alguna manera, que en nuestro pasaod común se transformaron en monstruos y seres mitológicos. Pero hay muchos otros temas que podrían tratarse igual, así que ya saben: si les gusta el post y quieren que abarque otras áreas, me avisan en los comentarios.

Aclaro desde ahora que este post no se va a quedar en los clásicos del canon occidental, que es en cierto modo reciente. Oh no, acá vamos a ir bien atrás, a civilizaciones que ya eran avanzadas cuando otras estaban averiguando cómo hacer el fuego. Todas estas culturas, sin excepción, han creado seres sobrenaturales que reflejan los mismos terrores básicos: la muerte, lo desconocido, el hambre, la enfermedad y el caos. Hoy les hablaré de los más famosos: el “depredador nocturno”, el “vampiro”, el “doppelganger” y su amiguito el “valle inquietante”, y el miedo al “principio femenino incontrolable”.

El Depredador Nocturno

Empezamos con el clásico de clásicos. El lobo feroz de los cuentos de hadas. Esto viene de Europa: simboliza peligros sexuales (violadores, tratantes de personas y demás). Un peligro frecuente del que había que advertir, y es por esto que las heroínas de estos cuentos suelen ser niñas o mujeres jóvenes, o en su defecto gente o animales muy ingenuos. Pero esto va mucho más lejos todavía.

El Adlet/Erqigdlet (pueblo Inuit, lo que conocemos por esquimales), por ejemplo. Son criaturas con cuerpo humano y piernas de perro/lobo, descendientes de una mujer que se apareó con un perro. Caníbales veloces que cazan en manadas bajo la luna. El miedo subyacente aquí es muy similar, sumándole el hambre en inviernos eternos y la delgada línea entre humanidad y bestialidad. Algunas personas creen que este mito dio origen al hombre-lobo como lo conocemos hoy, que es una versión nórdica. El Nahual (Mesoamérica), es un brujo o hechicero que puede transformarse en animal (coyote, jaguar, lobo) para devorar humanos o robar niños. Acá no es lo salvaje lo que asusta, el miedo subyacente aquí es la paranoia al "enemigo oculto" en la comunidad (¿tu vecino es un monstruo?). Me recuerda al cagüeiro cubano.

El Barghest (Folclore inglés, Yorkshire) también es un perro, pero de otro nivel. Específicamente estamos hablando de un perro negro fantasma del tamaño de un ternero, con ojos llameantes, que aparece antes de muertes violentas. A veces se le describe con garras de oso. ¿A qué les recuerda? Sí: es el mito que inspiró al Grim en Harry Potter y al Sabueso de los Baskervilles en Sherlock Holmes. El miedo subyacente aquí es muy obvio: la muerte como depredador inevitable.

Saliendo de los cánidos, caemos en otros bichos todavía más feos. El Ekek (Filipinas, mito pangasinense) es un humanoide con alas de murciélago y larga lengua que acecha de noche para lamer la piel de sus víctimas hasta dejarlas en carne viva. El miedo subyacente es muy… tropical: el peligro de dormir expuesto.

El Wendigo (Algonquinos, América del Norte) es un espíritu de hambre infinita que posee a quienes practican canibalismo. Nadie sabe exactamente cómo luce. Se te acerca de noche cuando estás a la intemperie, te llama por tu nombre, te lleva y nadie sabe lo que te hace, pero te vuelve loco. Cuando regresas, tú mismo eres un monstruo. ¿Podría ser una alegoría precolonial de la adicción o el consumismo desenfrenado? Ojo, un cuento con ese nombre, no recuerdo el autor, me tuvo sin dormir noches enteras y como figura folclórica ha aparecido hasta en Supernatural.

Aquí podemos ver patrones que se repiten: La hibridación humano-animal: todos mezclan rasgos humanos y bestiales, reflejando nuestro miedo a regresar a un estado salvaje. El acecho nocturno: atacan cuando estás vulnerable (durmiendo, perdido en el bosque). Son depredadores, no chupasangres: su objetivo es devorar, no solo parasitar (como los vampiros). ¿Por qué nos siguen aterrando? Bueno, claramente, por herencia evolutiva. El miedo a ser cazados por depredadores reales (lobos, grandes felinos) quedó grabado en nuestro ADN. Y claro, los volvimos metáforas de problemas más modernos: desde stalkers hasta el pánico al crimen callejero.

El Vampiro

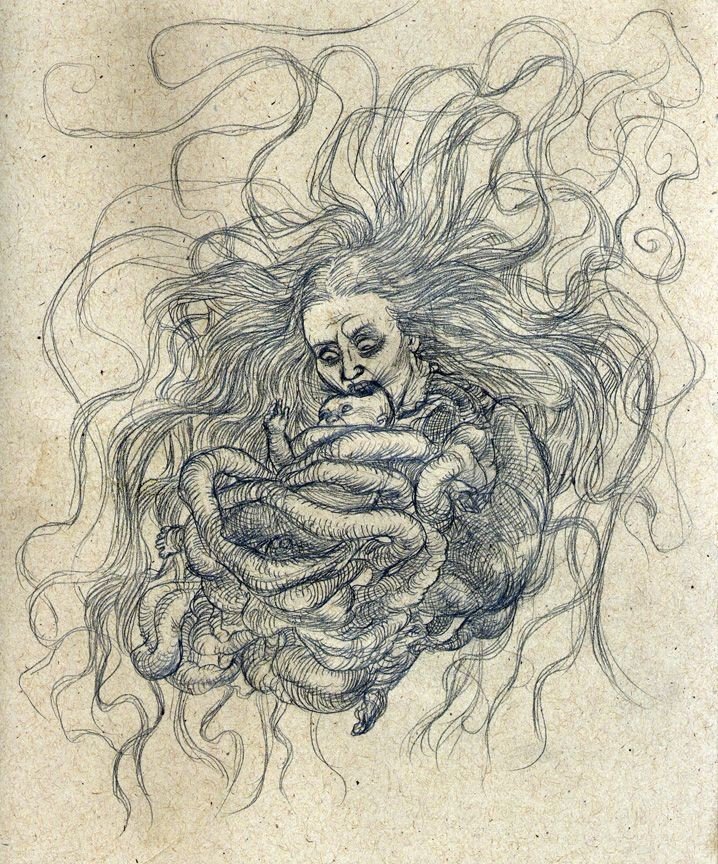

Picture by: Kurt Komoda

Todos conocemos al clásico vampiro de Europa Occidental, a lo Drácula, que en cierta medida es refinado y, bueno, humano (y que de acuerdo a todos los psicólogos representa el miedo a la sexualidad, ojito). Pero casi nadie conoce al vourdalak de Europa del Este, parte vital de este mito, que era bueno… un salvaje. En mi criterio, da más miedo. Un cuento llamado “El vourdalak” también me tuvo algunas noches sin dormir. Entonces, vamos a explorar variantes del arquetipo vampírico en distintas culturas, incluyendo no solo chupasangres clásicos, sino también espíritus, demonios y entidades que drenan la esencia vital de los vivos (alma, energía, aliento, o incluso su identidad).

El Yara-ma-yha-who (Aborígenes australianos) es un humanoide pequeño, rojo y sin pelo que vive en higueras. Espera a que pases bajo el árbol para caerte encima, chuparte la sangre con ventosas en sus dedos... y luego regurgitarte, repitiendo el proceso hasta convertirte en uno de ellos. Muy asquerosito todo. El miedo subyacente es, obviamente, el terror a ser comido por la naturaleza hostil (todos conocemos la fama de la fauna australiana).

En Filipinas, el El Aswang es un vampiro más bien caníbal, que ataca mayoritariamente recién nacidos y niños pequeños. Representa el miedo a la pérdida de hijos (mortalidad infantil, infanticidio, abortos espontáneos). El Jiangshi (China), es un cadáver rígido que se mueve dando saltos, vestido con ropas funerarias Qing. No chupa sangre, sino qi (energía vital) mediante su aliento helado. Surge cuando un alma no descansa (por muerte violenta o ritos fúnebres mal hechos). El miedo subyacente es perfectamente natural en la cosmovisión china: el respeto a los ancestros y el tabú de profanar tumbas.

La Penanggalan (Malasia/Tailandia), es la Cazadora de Partos: una mujer que practicó magia negra y puede separar su cabeza del cuerpo, arrastrando vísceras como tentáculos. Se alimenta de sangre de mujeres embarazadas o recién paridas. Vuela de noche, enredando sus tripas en árboles para esconderse, lo cual tiene que ser una visión que te mande directo al Más Allá pero del infarto. El miedo subyacente es el terror misógino al cuerpo femenino "monstruoso" y vulnerabilidad en el parto (alta mortalidad histórica).

La Loogaroo (Caribe, vudú haitiano) es una bruja que hace pacto con el diablo y por las noches se saca la piel para convertirse en una bola de fuego. Chupa sangre a través de un agujero en su víctima, dejándola anémica. Roba "fuerza vital" para mantenerse joven. Quizá simboliza el colonialismo y la explotación (¿símbolo de esclavistas que "chupaban" la vida de los pueblos?).

Por último, que si me dejan le dedico el post entero solo a los vampiros, el Alp (Alemania), un espíritu que toma forma de mariposa, perro o humano pálido. Se sienta sobre el pecho de los durmientes (pesadilla incubus), roba su aliento y bebe su leche materna o semen (fluidos vitales). Causa parálisis del sueño y sueños eróticos aterradores. El miedo es muy obvio: sexualidad reprimida y la violación nocturna. Es el precursor del Incubo/Súcubo y relacionado con el Sleep Paralysis Demon de internet.

Patrones comunes en el arquetipo vampírico: Fluidos = Vida. No solo sangre, también aliento, semen, leche, qi o sombra (en África, el Adze vampiriza la sombra del durmiente). La violación de lo sagrado: muchos surgen de muertes sin ritos, suicidios o profanaciones (ej.: Jiangshi por tumbas abiertas, Penanggalan por magia prohibida). El sexo, claro, siempre.

El Doppelgänger: El Doble Maldito

Picture by: Yaroslav Gerzherovich

Este es un miedo interesantísimo que suena moderno pero oh, no, no lo es. El término viene del folclore germánico/nórdico: El doppelgänger (literalmente "doble andante") era un espíritu o reflejo de una persona que aparecía como presagio de muerte o mala suerte. Verlo significaba peligro inminente. En literatura posterior, se convirtió en alguien que te roba la vida, o sea, vive peor que tú e intercambia su lugar contigo, ocupando tu buena vida y dejándote su mala suerte. Si eso no es miedo al inmigrante y al pobre que asciende socialmente, yo no sé qué es.

Pero esto viene de atrás. Los egipcios y mesopotámicos tenían la idea del ka (doble espiritual en Egipto) o el etemmu (fantasma en Mesopotamia) y sugerían que la identidad podía fragmentarse. Algunas tradiciones indígenas de muchas regiones hablan de "espíritus imitadores", que copian voces y formas para engañar a los vivos (ej.: el Skinwalker navajo). Los chinos no creen exactamente en esto, pero sí en fantasmas errantes que sustituyen las almas de los vivos cuando estos sufren un accidente traumático, y por eso tu pariente que despertó del coma “no parece el mismo” (ver el síndrome de Capgras, donde pacientes creen que sus seres queridos han sido reemplazados por impostores).

La psicología del terror al doble es curiosísima. Primero, la pérdida de identidad: el doppelgänger desafía la noción de que somos seres únicos. Si hay un "yo" idéntico, ¿quién es real? También la culpa y sombra (Jung): el doble a menudo encarna lo reprimido (ej.: Dr. Jekyll y Mr. Hyde). Hoy, esto se refleja en personajes como Tyler Durden (El Club de la Lucha).

Y ahí caemos en el amiguito del doppelgänger, el ** Valle Inquietante (Uncanny Valley)**. Esto es un término acuñado por el roboticista Masahiro Mori (1970) para describir la repulsión que sentimos hacia robots o animaciones casi humanos, pero no del todo (ej.: androides, CGI hiperrealista, muñecas realistas).

¿Por qué nos asusta una IA cuya voz es “demasiado humana”? Primero, crea Disonancia cognitiva: el cerebro detecta anomalías en rasgos faciales o movimientos (ej.: sonrisas sin arrugas en los ojos, parpadeo no natural) y hace cortocircuito con lo que tenemos grabado a fuego que debe ser un humano. Incertidumbre evolutiva: en la prehistoria, identificar humanos "falsos" (enfermos, zombis, espíritus) era clave para sobrevivir. Miedo a lo no-muerto: El valle inquietante evoca cadáveres, autómatas o posesiones (como los gólems judíos). La conexión entre ambos conceptos es muy obvia: El doppelgänger es el valle inquietante en forma humana: Ambos juegan con la idea de que algo casi idéntico a nosotros es, en el fondo, una amenaza.

Y ya, para cerrar el post:

La "Mujer Monstruo": El miedo arquetípico a lo femenino

Imagen: Pinterest, ni idea el autor.

A lo largo de las culturas, la figura femenina ha sido asociada tanto con la creación como con la destrucción, dando lugar a monstruos que encarnan los miedos más profundos hacia la sexualidad, la maternidad y el poder de la mujer. Estos seres son manifestaciones de tabúes sociales, misoginia ancestral y terror sagrado ante lo incontrolable. El ejemplo más clásico es Medusa (Grecia), una mujer violada y castigada por Atenea (otra mujer, hay que ser…), cuyo rostro convierte en piedra a quien la mira. El miedo subyacente es el terror a la víctima que no se queda como víctima, la víctima que no quiere dar lástima sino hacer justicia. ¡Cuánto miedo le tienen, ancestralmente, a eso!

Pero hay más. Oh, muchas más.

Tlazoltéotl (Azteca), era la Diosa de la purificación y el pecado, se alimenta de "suciedad moral" (adulterio, incesto). Representa el miedo a la mujer como contaminadora de linajes. En otras palabras, la hija o esposa que no se queda quietecita en casa, sino que puede salir a provocar “problemas”. Como Lilith, ¿recuerdan a Lilith? Por eso, hoy es reinterpretada como diosa de la liberación sexual en algunas ramas del neopaganismo.

La mujer como caos en contraposición al hombre como orden, es algo muy viejo. Ahora, hacer monstruosa o mala a dicha mujer ya es extremo… pero normal. Rangda (Bali), no solo es el caos sino que se representa como una líder de brujas que se alimenta de niños y baila en cementerios. El miedo subyacente no es solo el poder femenino desatado, sino la mujer que no es maternal, que no ejerce como figura protectora de niños, algo que en nostras se ve como “natural”. Por eso también hay fantasmas como La Llorona, ¿qué puede ser más terrible que una madre que daña a sus propios hijos? Y ese arquetipo de la madre asesina se repite muchísimo.

Luego vamos a otra arista de lo femenino y conocemos a la Kuchisake-onna (Japón). Es un espíritu con la boca cortada de oreja a oreja que pregunta "¿Soy bonita?" antes de asesinar. El miedo subyacente obvio es la belleza femenina como trampa mortal (relacionado con el mito de la femme fatale). O la Pomba Gira (Brasil, Umbanda), un espíritu que defiende a las prostitutas y mujeres transgresoras que concede deseos... a un precio. El miedo a la sexualidad femenina independiente, no reprimida como algo diabólico.

Por supuesto, hay patrones en la "Mujer Monstruo". Como no podría ser de otra manera, Sexualidad = Peligro. Muchas son castigadas por ser deseables (Medusa) o desear (Pomba Gira). La Maternidad Monstruosa: desde infanticidio (Llorona) hasta canibalismo (Rangda). El Poder Chamánico: las brujas, por ejemplo, son demasiado poderosas y manejan magias inaccesibles a los hombres. Y todos sabemos cuánto les gusta que algo se salga de su control.

Today’s topic, "Ancient Myths from Diverse Cultures Affecting Our Psychology, Narratives, and Worldview," is one I love because it can be analyzed from countless angles. Today, I’ll talk about fear—those archetypal terrors, so to speak, that in our shared past transformed into monsters and mythological beings. But there are many other themes we could explore, so if you like this post and want me to cover other areas, let me know in the comments.

I’ll clarify right away that this post won’t stick to the classics of Western canon, which is, in a way, relatively recent. Oh no, we’re going way back—to civilizations that were already advanced while others were still figuring out how to make fire. Without exception, all these cultures have created supernatural beings that reflect the same basic fears: death, the unknown, hunger, disease, and chaos. Today, I’ll discuss the most famous ones: the "nocturnal predator," the "vampire," the "doppelgänger" and its buddy the "uncanny valley," and the fear of the "uncontrollable feminine principle."

The Nocturnal Predator

We start with the classic of classics—the Big Bad Wolf from fairy tales. This comes from Europe, where it symbolizes sexual dangers (rapists, human traffickers, etc.). It was a frequent threat that needed warning about, which is why the heroines in these tales are often young girls or naive individuals. But this goes much further.

Take the Adlet/Erqigdlet (Inuit, what we commonly call Eskimos), for example. These creatures have human bodies and dog/wolf legs, descendants of a woman who mated with a dog. They are fast, cannibalistic, and hunt in packs under the moon. The underlying fear here is very similar, with the added terror of starvation during endless winters and the thin line between humanity and bestiality. Some believe this myth gave rise to the werewolf as we know it today, which is a Norse version.

Then there’s the Nahual (Mesoamerica), a sorcerer who can shapeshift into an animal (coyote, jaguar, wolf) to devour humans or steal children. Here, it’s not the wild that scares people—the underlying fear is paranoia about the "hidden enemy" in the community (Is your neighbor a monster?). It reminds me of the Cuban cagüeiro.

The Barghest (English folklore, Yorkshire) is also a dog, but on another level. Specifically, we’re talking about a ghostly black dog the size of a calf, with flaming eyes, that appears before violent deaths. Sometimes it’s described with bear claws. Sound familiar? Yes—it’s the myth that inspired the Grim in Harry Potter and the Hound of the Baskervilles in Sherlock Holmes. The underlying fear here is obvious: death as an inevitable predator.

Moving beyond canines, we encounter even uglier creatures. The Ekek (Philippines, Pangasinan myth) is a humanoid with bat wings and a long tongue that lurks at night, licking its victims' skin until they’re raw. The underlying fear is very… tropical: the danger of sleeping exposed.

The Wendigo (Algonquian, North America) is a spirit of infinite hunger that possesses those who practice cannibalism. No one knows exactly what it looks like. It approaches you at night when you’re out in the open, calls your name, takes you away—and no one knows what it does to you, but it drives you mad. When you return, you yourself become a monster. Could this be a precolonial allegory for addiction or unrestrained consumerism? A story with that name (I don’t recall the author) kept me awake for nights, and as a folkloric figure, it’s even appeared in Supernatural.

Here, we see recurring patterns: Human-animal hybridization: All blend human and beastly traits, reflecting our fear of reverting to a savage state. Nocturnal stalking: They attack when you’re vulnerable (sleeping, lost in the woods). They are predators, not parasites: Their goal is to devour, not just leech (unlike vampires).

Why do they still terrify us? Well, clearly, because of evolutionary heritage. The fear of being hunted by real predators (wolves, big cats) is etched into our DNA. And of course, we’ve turned them into metaphors for more modern issues—from stalkers to street crime panic.

The Vampire

We all know the classic Western European vampire, à la Dracula—refined and, well, human (and according to psychologists, representing the fear of sexuality). But almost no one knows the vourdalak from Eastern Europe, a crucial part of this myth, who was… well, a savage. In my opinion, it’s much scarier. A tale called "The Vourdalak" also kept me up a few nights.

So, let’s explore variations of the vampire archetype across cultures, including not just classic bloodsuckers but also spirits, demons, and entities that drain the life essence of the living (soul, energy, breath, or even identity).

The Yara-ma-yha-who (Australian Aboriginal) is a small, red, hairless humanoid that lives in fig trees. It waits for you to pass underneath, drops on you, sucks your blood with suction-cup fingers… then regurgitates you, repeating the process until you become one of them. Pretty disgusting. The underlying fear is, obviously, the terror of being consumed by hostile nature (we all know Australia’s fauna reputation).

In the Philippines, the Aswang is more of a cannibalistic vampire, preying mostly on newborns and small children. It represents the fear of losing children (infant mortality, infanticide, miscarriages).

The Jiangshi (China) is a stiff corpse dressed in Qing funeral clothes that moves by hopping. It doesn’t drink blood but absorbs qi (life energy) through its icy breath. It arises when a soul doesn’t rest (due to violent death or improper funeral rites). The underlying fear is perfectly natural in Chinese cosmology: respect for ancestors and the taboo of grave desecration.

The Penanggalan (Malaysia/Thailand) is the Birth Hunter—a woman who practiced black magic and can detach her head, dragging her entrails like tentacles. She feeds on the blood of pregnant women or new mothers. She flies at night, wrapping her intestines around trees to hide—an image that could send you straight to the afterlife via heart attack. The underlying fear is misogynistic terror of the "monstrous" female body and the vulnerability of childbirth (historically high mortality rates).

The Loogaroo (Caribbean, Haitian Vodou) is a witch who makes a pact with the devil and, at night, removes her skin to become a fireball. She sucks blood through a hole in her victim, leaving them anemic. She steals "life force" to stay young. Perhaps she symbolizes colonialism and exploitation (a metaphor for slave masters who "sucked" the life from people?).

Finally—because if I don’t stop, I’ll dedicate the whole post to vampires—there’s the Alp (Germany), a spirit that takes the form of a butterfly, dog, or pale human. It sits on sleepers’ chests (incubus nightmare), steals their breath, and drinks their breast milk or semen (vital fluids). It causes sleep paralysis and terrifying erotic dreams. The fear here is obvious: repressed sexuality and nocturnal violation. It’s the precursor to the Incubus/Succubus and related to the Sleep Paralysis Demon of internet lore.

Common patterns in the vampire archetype: Fluids = Life: Not just blood but also breath, semen, milk, qi, or even shadow (in Africa, the Adze vampirizes a sleeper’s shadow). Violation of the sacred: Many arise from deaths without rites, suicides, or desecration (e.g., Jiangshi from disturbed graves, Penanggalan from forbidden magic). Sex, of course. Always.

The Doppelgänger: The Cursed Double

This is a fascinating fear that sounds modern but—oh no—it’s not. The term comes from Germanic/Norse folklore: The doppelgänger (literally "double walker") was a spirit or reflection of a person that appeared as an omen of death or misfortune. Seeing it meant imminent danger. In later literature, it became someone who steals your life—living worse than you and swapping places, taking your good life and leaving you their bad luck. If that’s not fear of immigrants and the poor rising socially, I don’t know what is.

But this goes way back. Egyptians and Mesopotamians had the concept of the ka (spiritual double in Egypt) or the etemmu (ghost in Mesopotamia), suggesting identity could fragment. Many indigenous traditions speak of "imitator spirits" that copy voices and forms to deceive the living (e.g., the Navajo Skinwalker). The Chinese don’t exactly believe in this, but they do have wandering ghosts that replace the souls of the living after traumatic accidents—which is why your relative who woke up from a coma "doesn’t seem like themselves" (see Capgras syndrome, where patients believe loved ones have been replaced by impostors).

The psychology of the terror of the double is fascinating:

- Loss of identity: The doppelgänger challenges the notion that we are unique. If there’s an identical "me," who’s real?

- Guilt and the shadow (Jung): The double often embodies the repressed (e.g., Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde). Today, this is reflected in characters like Tyler Durden (Fight Club).

And this brings us to the doppelgänger’s buddy: the Uncanny Valley. Coined by roboticist Masahiro Mori (1970), it describes the revulsion we feel toward robots or animations that are almost human but not quite (e.g., androids, hyper-realistic CGI, lifelike dolls). Why does an AI with a "too-human" voice unsettle us?

- Cognitive dissonance: The brain detects anomalies in facial features or movements (e.g., smiles without eye wrinkles, unnatural blinking) and short-circuits.

- Evolutionary uncertainty: In prehistory, identifying "fake" humans (sick, zombified, spirits) was key to survival.

- Fear of the undead: The uncanny valley evokes corpses, automatons, or possessions (like Jewish golems).

The connection between the two concepts is obvious: The doppelgänger is the uncanny valley in human form. Both play with the idea that something almost identical to us is, deep down, a threat.

The "Monstrous Woman": The Archetypal Fear of the Feminine

Across cultures, the feminine figure has been associated with both creation and destruction, giving rise to monsters that embody the deepest fears of sexuality, motherhood, and female power. These beings manifest social taboos, ancestral misogyny, and sacred terror of the uncontrollable.

The most classic example is Medusa (Greece), a raped woman punished by Athena (another woman—go figure), whose gaze turns people to stone. The underlying fear is terror of the victim who refuses to stay a victim, the victim who doesn’t want pity but justice. How ancestrally terrifying is that?

But there’s more. Oh, so much more.

Tlazoltéotl (Aztec) was the Goddess of Purification and Sin, feeding on "moral filth" (adultery, incest). She represents the fear of women as contaminators of bloodlines—in other words, the daughter or wife who doesn’t stay quietly at home but goes out and causes "trouble." Like Lilith, remember her? That’s why today, she’s reinterpreted as a goddess of sexual liberation in some neopagan branches.

The woman as chaos, in contrast to the man as order, is an ancient trope. But making her monstrous or evil takes it to the extreme… yet it’s normalized. Rangda (Bali) isn’t just chaos—she’s depicted as a witch leader who devours children and dances in cemeteries. The underlying fear isn’t just unleashed female power, but the woman who isn’t maternal, who doesn’t act as a protector of children—something seen as "natural" in women. That’s why there are also ghosts like La Llorona—what could be more terrifying than a mother who harms her own children? And that murderous mother archetype repeats endlessly.

Then there’s another facet of the feminine: Kuchisake-onna (Japan), a spirit with her mouth slit ear to ear who asks, "Am I pretty?" before killing. The obvious underlying fear is female beauty as a deadly trap (tied to the femme fatale myth). Or Pomba Gira (Brazil, Umbanda), a spirit who defends prostitutes and transgressive women, granting wishes… for a price. The fear of independent, unrepressed female sexuality as something diabolical.

Of course, there are patterns in the "Monstrous Woman": Sexuality = Danger: Many are punished for being desirable (Medusa) or desiring (Pomba Gira). Monstrous Motherhood: From infanticide (La Llorona) to cannibalism (Rangda). Shamanic Power: Witches, for example, are too powerful, wielding magic inaccessible to men. And we all know how much they hate when something slips their control.

¡Aplausos ante este estudio que nos compartes!

¡Gracias por ello!

De hecho dudaba entre varios temas. Elegí el miedo porque me gustaba más, pero hay varios. Si les interesa que sigan me dicen, y voy subiendolos poco a poco

¡Por supuesto que nos interesan!

Lo comparto 👏🫂✨

Gracias!

Y tú, ¿con cuál te identificas más o en cuál te convertirías?

!BBH

Yo sería una entidad femenina del caos.

Te asienta sí 😅 aunque contradictorio serías la entidad del caos más organizada 🤣

Y quizá si fuera de caos se me quitaría el TOC 🤣

!!Muy bueno!!

Gracias!

Congratulations @gaviotawriter! You have completed the following achievement on the Hive blockchain And have been rewarded with New badge(s)

You can view your badges on your board and compare yourself to others in the Ranking

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOP