The Death of Oda Nobunaga

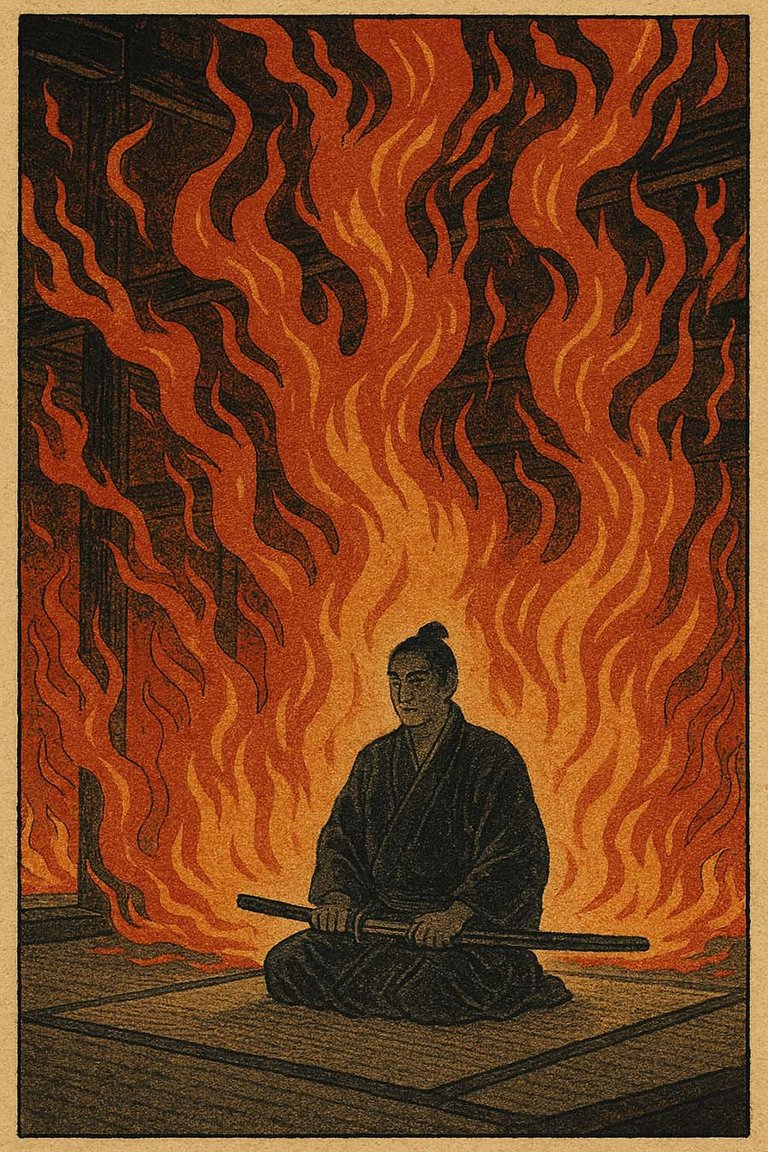

On this day in 1582, one of Japan’s most feared and transformative warlords was betrayed and killed in a Kyoto temple. Oda Nobunaga, known equally for his ruthlessness and his revolutionary vision, died by seppuku in the burning halls of Honnō-ji, a temple that should have been his sanctuary.

His story didn’t end there — it never really does with Nobunaga. He’s been cast as a demon, a genius, a proto-modernist, even a tragic hero. But to understand his death, we have to understand what he was trying to build and why so many wanted to stop him.

A Brief Life of Fire

Oda Nobunaga was born in 1534, the second son of a minor warlord in Owari Province. The Sengoku period (the “Warring States” era) was chaos incarnate, a time of fractured authority, endless battles, and shifting alliances.

From a young age, Nobunaga stood out for his erratic, almost anarchic energy. He wore eccentric clothes, disrespected social norms, and acted like a fool. He was, in fact, nicknamed “The Fool of Owari” (尾張の大うつけ).

But then he stopped being the fool. He took control of Owari and his ambition grew. He rose through cunning, brutality, and luck, conquering one rival after another and showing little mercy to those who defied him. His most infamous act was the near-total annihilation of the warrior-monk stronghold at Mount Hiei in 1571, where he slaughtered thousands of Buddhist monks, women, and children. Many saw it as mass murder. Nobunaga saw it as clearing the path.

He once said, “The strong eat, the weak are meat.” This was not metaphor.

It is mainly because of that Mount Hiei episode but also other acts of ruthlessness that his nickname became “The Demon of Owari” (尾張の大魔王) and “The Demon King” (魔王), and above all else he is remembered to this day as a bloodthirsty tyrant.[1]

Breaking the Old World

But the reality is, Nobunaga was not merely a brute or a savage hellbent on slaughter. He was also a visionary. He:

- Broke the power of Buddhist institutions that had long meddled in politics.

- Embraced firearms and reorganized his armies around them — decades ahead of his European counterparts.

- Encouraged trade and welcomed Jesuit missionaries, not necessarily out of piety but as a counterbalance to domestic powers.

- Sought to unify all of Japan under a single military authority — his own.

And he might have done it, had it not been for Akechi Mitsuhide.

Honnō-ji: The Betrayal

On June 21, 1582, Nobunaga was staying at Honnō-ji temple in Kyoto. He was unguarded — just a few dozen retainers, no full army. He was preparing to join Toyotomi Hideyoshi in a campaign against the Mōri clan.

But one of his own generals, Akechi Mitsuhide, had other plans.

Why Mitsuhide betrayed him is still debated. Some say it was a personal grudge — Nobunaga had humiliated him repeatedly. Others suggest political motives, or perhaps a fear that Nobunaga’s dominance would soon consume even his allies.

Whatever the reason, Mitsuhide struck. His troops surrounded the temple at dawn.

Outnumbered and outflanked, Nobunaga knew he had no escape. He fought briefly, then retreated to the inner quarters and performed seppuku — ritual suicide — setting the temple ablaze around him. His last words, if any, are lost to history. His body was never found.

His heir, Nobutada, was also attacked and killed the same day.

A Legacy That Refused to Burn

Nobunaga’s death should have ended his dream of unifying Japan. But it didn’t. Mitsuhide ruled for just thirteen days before he was hunted down and killed by Hideyoshi, one of Nobunaga’s most loyal generals. In the power vacuum that followed, Hideyoshi rose, and then Tokugawa Ieyasu after him. Together they completed what Nobunaga began.

It wasn’t quite that simple, of course. Things never are. For one, Ieyasu wasn’t at all friendly with Hideyoshi and moved against him before being advised (in part by Nobukatsu, another of Nobunaga’s sons) to bend the knee and bide his time. But the end result was a direct legacy from Nobunaga to Hideyoshi and then to Ieyasu.

In that sense, Nobunaga was both the destroyer of the old world and the architect of the new. He didn’t live to see Japan unified, but it couldn’t have happened without him.

On this anniversary, we remember the fire — both literal and metaphorical — that consumed Oda Nobunaga. A tyrant, a trailblazer, a man far ahead of his time. His death marked the end of one era and the beginning of another.

What do you think? Was he a monster or a modernizer? Or both?

-

These demon titles or nicknames seem to come from a letter Nobunaga sent to Takeda Shingen, which he signed as 第六天魔王 — “Nobunaga, Demon King of the Sixth Heaven.” In Buddhist cosmology, the sixth heaven is the highest of the desire realms, inhabited by powerful deities. By adopting this title, Nobunaga was likely trying to intimidate Takeda, implying that his power transcended human limits and that he was unstoppable by any mortal man. ↩

❦

|

David is an American teacher and translator lost in Japan, trying to capture the beauty of this country one photo at a time and searching for the perfect haiku. He blogs here and at laspina.org. Write him on Mastodon. |

He was a ruthless leader, which is how most very successful conqueror's have been throughout history. In the end he was betrayed, and his general must have had his sights on even greater power. Or he just didn't like him like you mentioned. Interesting story, very cool!