An Autumn Moon Above Edo: Bashō at Thirty-Three

As the guest in a linked-verse gathering in Iga, a young Bashō gave the following opening haiku:

nagamuru ya Edo niha marena yama no tsuki

the mountain moon is rare

in worldly Edo

—Bashō

Bashō was just 33 when he wrote this. He had been struggling for four years to survive in Edo and was now back in Iga, his hometown. While there, he was invited to a renga session[1] and, as the honored guest, gave the opening verse: this haiku.

On the surface, he's offering a very simple image. The phrase yama no tsuki, "mountain moon", was a classical image in Chinese and Japanese poetry, evoking purity, solitude, and nature. A fitting, elegant beginning.

But dig deeper, and Bashō’s cleverness shines.

The word Edo (江戸) refers to what is now Tokyo — already the de facto capital by 1676. It puns on Edo (穢土), a Buddhist term meaning the impure land of earthly desire. It’s the place of attachment and suffering, where enlightenment is obstructed.

So when Bashō says the mountain moon is “rare in Edo,” he’s saying more than the city lacks natural beauty. He’s also suggesting that enlightenment, and the serene clarity it symbolizes, is hard to come by in a world of ambition, noise, and appetite.

After living as a struggling artist in the city, he may have had some bitterness, but moreover he’s following the etiquette of the renga world and of Japanese culture in general: praising the host’s rural setting while humbling himself as a traveler from the big city. Everyone in the room would have caught the gesture and the double meaning, and appreciated both.

This was the Danrin period of Bashō’s development, when his style was witty and full of wordplay. Later, he would grow dissatisfied with mere cleverness and find such displays distasteful. But here, in this early verse, you can already see him balancing elegance, depth, and social finesse.

And perhaps there’s one final twist. On the surface, he is being modest and praising his host and the rural beauty, yet implicitly elevating his own sensibility for being able to appreciate it. A bold move, but one that perfectly fits with the Danrin school and with young Bashō.

This isn’t usually considered one of his best haiku, but I like it. It shows off the cleverness that served him well when he was climbing to the top of the haiku world. And it’s a telling glimpse of what he would later reject. A good poem for marking his haiku journey.

❦

|

David is an American teacher and translator lost in Japan, trying to capture the beauty of this country one photo at a time and searching for the perfect haiku. He blogs here and at laspina.org. Write him on Bluesky. |

Very nice - the intrigue of just a few words.

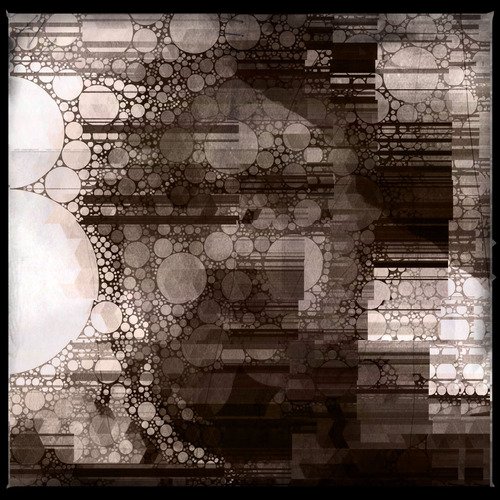

I'm curious, did he also paint the landscape scene?

No, that was a woodblock artist. Completely separate professions.

!GIFU

(1/5)

@dbooster! @epic-fail wants to share GiFu with you! so I just sent 20.0 SWAP.GIFU to your account on behalf of @epic-fail.

Ah, a bit of double meaning there! Quite clever!

江戸には稀な山の月

芭蕉の歌はいいですよねぇ 🌕️

!wine

!HUG 😄🙌

I like that painting.. something about it.. so serene.

That's the beauty of woodblock prints!